Stephen Antonson’s chandeliers hang in elegant homes across the globe. His tables are in President Barack Obama’s private residence. His designs sell for tens of thousands of dollars.

The Michigan native has come a long way since graduating from Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Art, yet he still makes his stunning plaster furniture and furnishings the same way he worked as a student: “On my hands and knees, mucking around.”

Antonson’s Brooklyn-based studio is a testament to his playful, messy methods. On any given afternoon, the concrete floor is covered in a layer of white dust, the result of Antonson’s sanding the snow-white chandeliers, lamps and tables that have put him on the art and design cognoscenti’s map.

Louis Bofferding, one of Manhattan’s premier fine art dealers, has visited Antonson’s studio, and describes the artist’s atelier “like the abandoned dacha of Dr. Zhivago.”

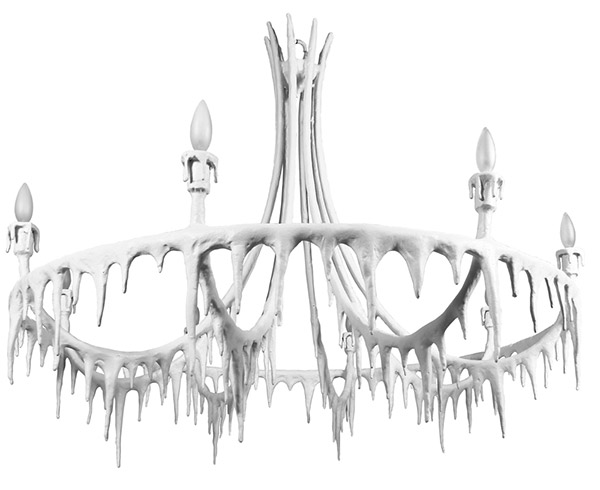

Indeed, one of Antonson’s first designs was a chandelier dripping with icicles, each one attached and plastered by hand. It’s the human touch that distinguishes his pieces. In an Architectural Digest profile of him appropriately titled “White Magic,” writer Mitchell Owens describes how Antonson “transforms humble plaster into objects of surreal beauty.”

“I am an artist,” Antonson said. “It just so happens that I also design objects that are functional.” He credits having studied “everything — painting, welding, photography, video, you name it” at CMU’s School of Art, where he earned his degree in 1989, for his ability to marry art and design. The results are chandeliers and sconces that the blog Remodelista describes as items “that Gertrude Stein might have hung in her Paris salon to illuminate her Picassos.”

It’s a lofty compliment, yet Antonson is quick to point out that he spends his days working with his hands, thus the company name “Stephen Antonson By Hand.” He touches every single piece before it leaves his studio, starting with a sketch and ending with a work of art. Once he is happy with a pencil drawing, he assembles the wood, clay or metal frame that will form its skeleton. Later, he paints on the plaster — a milky liquid when wet — with a brush, allows it to dry and finally sculpts and sands it to a smooth, matte finish. He repeats the painstaking process dozens of times, creating pieces simultaneously, sanding and sculpting some while others dry.

While his designs can take weeks and even months to complete, his process ensures that each piece is distinctive, down to the imprints of his fingers left on the surface.

“It separates me from the crowd,” he said. “People can see those marks and say, ‘Wow, this person was right here.’”

His plaster work sometimes goes beyond furniture, such as a recently commissioned pair of six-foot tusks, which now resides in a glamorous Las Vegas hotel lobby.

He gives much credit for his innovative work to lessons learned at CMU.

“My painting professor, Susanne Slavick, really pushed us to fail spectacularly. She told us that the more we failed, the better grade we’d get, and it really loosened everybody up. It was genius. Any successful cook, writer or businessperson will tell you the same thing. It comes down to innovation — the people who listen to the feedback from the process of failing are the ones that succeed.”

Slavick, the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Art, remembers Antonson’s willingness to take risks and his witty disposition. Both were on full display during Pittsburgh’s 2010 Three Rivers Arts Festival, where Antonson deployed an outsized inflatable of Andrew Carnegie in snorkel and mask, titled Sink or Swim, in the Allegheny River.

“Stephen infuses his creations with both elegance and humor,” Slavick said. “whether they are functional or winsomely absurd.”