Javed Saifullah Khan boards a plane bound from Karachi, Pakistan, to Pittsburgh, Pa. Prepared for his freshman year at Carnegie Mellon University, he carries a suitcase and some advice from his mother:

Don’t ski. (No wonder. When his father was a student, he broke his leg while skiing.)

Don’t go to the beach.

Don’t get married.

Don’t fail.

On the flight, he thinks, “Okay, I won’t ski. I won’t go to the beach. And I won’t get married—why would I get married? I’m 17!”

Then he thinks, “Of course I won’t fail. I’m not going to America to fail.”

That was in the fall of 1968. Today, Javed Khan is chairman of the SAIF Group, one of Pakistan’s leading industrial and service conglomerates, which generates annual revenues of more than $300 million.

Although headlines about Pakistan often announce tales of violence and poverty, Khan’s story is a reminder that a nation is more than its media clips. His story also makes clear the importance of educating global citizens, a trend that has gained traction since his days at Carnegie Mellon, as the world grows increasingly interconnected. Educators often say the best way to understand the benefits of this type of learning is to listen to the stories of students themselves, how they perceive themselves as “citizens of the world.”

Khan says he understands what that means. Even though he has deep philosophical differences with the United States on some issues, including the Afghan War, he knows it’s more productive to engage in discussion than to stand on the polarized ground of “us” versus “them.” Global education allows for this kind of conversation, collaboration, and compromise—processes that Khan began at CMU and now finds indispensable in his work.

The SAIF industrial story actually began in 1920s when Khan’s grandfather, a significant landowner, became India’s biggest Muslim government contractor and built a power plant.

Subsequently, Khan’s father, who was sent to London to train as a barrister, ended up starting a canning business after the outbreak of WW II, which became a supplier to the British Indian Army.

By the time Javed Saifullah Khan was born in Peshawar in 1951—four years after Pakistan became an independent nation—the family business was firmly established. For him, childhood meant playing on the lush two acres at his house with his four brothers, games of cricket with cousins, summers at their second home, studying at the finest schools. But the dreamy landscape was fleeting. His father died in 1964, when he was just 13.

The business could have folded then. But his mother, Begum Kulsum Saifullah Khan, immediately took over operations of the company and secured a permit to set up a textile mill.

“If I start talking about her,” Khan says, “I could talk until six o’clock in the morning. After my father died, she became a father, a mother, an advisor, and a friend.” The entire grieving family was likewise resilient: Khan and his brother went to the Peshawar library and researched the best schools in the United States. Carnegie Mellon University was at the top of their list. Khan’s older brother, Salim, enrolled in what was then the Carnegie Institute of Technology and left for Pittsburgh. In 1968, he earned his BS in engineering.

The sons had a powerful role model in their mother. In fact, in addition to running the company, Begum Kulsum was a founding member of the Women's Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Pakistan Association of Women Entrepreneurs. She became the first female federal minister, published an autobiography, and was eventually granted the Hilal-i-Imtiaz—one of Pakistan’s highest civilian awards. Before she passed away in early 2015, her son says, she taught her children that “women were also human beings—not just beasts of burden.” In a time and place where feminism was not common currency, Begum Kulsum showed her sons that women could do the same things as men.

“She literally wore pants in the morning as she went to work,” Khan says, “then she came home and took care of us.”

When it was Javed Khan’s turn to attend Carnegie Mellon, he knew the school would give him the tools for a similarly successful career. His mother agreed. Apart from her four prohibitions, Khan’s mother encouraged him to do anything else he set his mind to—Khan says that kind of freedom gave him confidence. The economics and history major graduated in 1972. A year later, after earning an MBA at the University of Pittsburgh, he moved back to Pakistan and joined his family business; but, in 1979, he settled in New York in order to promote the family’s textile operation. When he returned to Islamabad for a holiday in 1981, his mother convened a family meeting. Until that point, Salim had been running the business alongside their mother, but now, he announced, he was going to be sworn in as minister of finance for the province. Khan immediately wondered: “Who the hell is going to take care of business?”

Everybody looked at him. “That was it,” says Khan.

Javed Khan was 30 years old when the family entrusted the company to him. The new chairman of SAIF Group returned to the States to pack up his belongings and say goodbye to friends. He has lived in Islamabad ever since, 34 years and counting.

Today, Carnegie Mellon offers degrees in nearly 20 locations around the world and encourages all students to become engaged citizens who help to solve both local and international issues. Humera Afridi, a Pakistani-born writer, believes that telling stories like that of the Khan family is essential to this new global paradigm. Afridi studied in the Literary and Cultural Theory program at Carnegie Mellon, earning her MFA in 1996; now at work on a novel, she lives in New York City and has written about her homeland for international publications. In one of her essays, “A Gentle Madness,” she describes her love for Pakistan’s evolving nature. To be Pakistani, she writes, is to be “brushing against a past whose paint hasn’t quite dried on the canvas for the present is perpetually being recreated.” This was especially true when Javed Khan took over business operations during the tumultuous years of the Soviet-Afghan War. In an unstable economic climate, he painstakingly expanded the family’s canning company. The SAIF Group now employs 5,000 people and comprises five subsidiaries and six associate companies, as well as two nonprofit groups. “It’s heartening all around to be able to read a success story coming out of Pakistan,” says Afridi. “All we hear is gloom and doom. That’s not an exaggeration, but there are also plenty of positive, amazing stories.”

Carnegie Mellon helped shape both Afridi’s and Khan’s stories. When Khan began his work in Pakistan, he noticed three ways his CMU education influenced his approach. For one thing, he knew how to confidently express himself. In eighth-grade algebra class in Peshawar, he always knew the answers, but the teacher would say, “Saifullah, keep quiet.” It follows that when Khan was a freshman at CMU, he was quiet in classes, assuming he would annoy professors if he raised his hand. “But when I didn’t do well on midterms, my teacher said, ‘You didn’t participate in class discussions.’ That was when I started asking questions.” He took a public speaking class, trembling at the podium, worried that people wouldn’t understand his thick accent. But with practice, he learned to communicate perfectly. “And I learned to look people in the eye,” he says.

As he was looking people in the eye, he was also maximizing his international experience. In Pittsburgh, he developed a knack for putting people at ease. He made sure to learn about Thanksgiving, Christmas, Valentine’s Day—cultural markers that allowed him to connect with Americans. Khan still has a U.S. driver’s license and a house in Virginia, and he values his ability to move between cultures, keeping his business global.

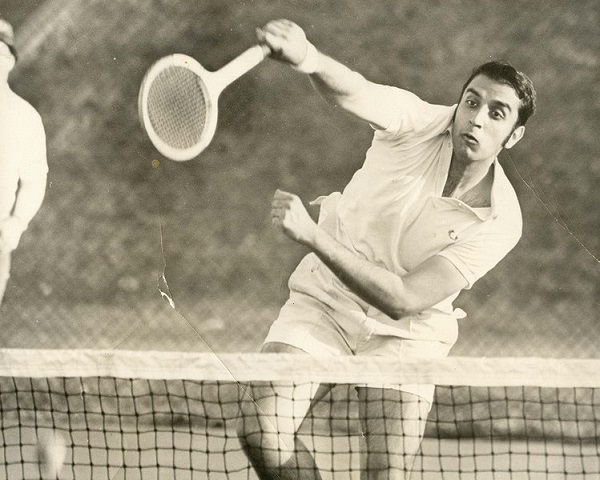

But CMU wasn’t just about work. He fondly remembers going to TGIF parties on the Cut (a grassy area in the center of campus) and putting away his books for the weekend. He also played on CMU’s tennis team and was named “most valuable player” for three different seasons. To this day, he finds life balance essential: “You work very hard, but then you also relax.”

Although he might allow himself time to relax, the success of the SAIF Group makes it clear that he’s been working hard. The conglomerate is diverse—but Khan explains that one thread ties it together: spotting a need and trying to do something new to fill it.

Pakistan is the world’s fourth largest producer of cotton, so it’s no surprise that Khan’s mother pinpointed textiles as the business’s core. Today, the Mediterranean Textile Company and the SAIF and Kohat Textile Mills produce high-quality yarn for premium European shirt manufacturers.

From there, the company branched out with SAIF Power and SAIF Energy. It was also the first to bring GSM phone service to Pakistan, in a 1994 venture with Motorola. “In business,” Khan says, “you have to see what’s the next big thing.” For SAIF, another next big thing was bandwidth, so SAIF’s subsidiary Transworld Associates installed the region’s first private sector undersea fiber optic cable, running among Pakistan, Oman, and United Arab Emirates. And through its Softech Systems based in Lahore, SAIF exports financial software to Nigeria, the United States and other countries worldwide. In recent years, Islamabad has gone from one golf course to six. Taking advantage of this boom, SAIF’s associated company Elite Estate is currently developing high-end real estate with an Egyptian partner.

But the population that can afford luxury apartments is much smaller than the population that can’t. Many of Pakistan’s nearly 200 million citizens live on subsistence agriculture; the average income is about $1,500 per year. In what Afridi calls a “divided, stratified society,” SAIF works across the spectrum, helping to take care of the Pakistani people and environment. SAIF Healthcare runs the Kulsum International Hospital, a comprehensive full-service care facility. The Saifullah Khan Trust provides financial help for higher education to poor Pakistanis. Lahore Compost sorts waste, producing more than 50,000 metric tons of compost annually. It’s the first project of its kind on such a large scale in Pakistan.

And what of that “gloom and doom” Afridi refers to? In a country where the Taliban is active, where 1,000 women die from honor killings each year, where the literacy rate is only 25%, how can one family make a positive impact? It’s true, Afridi says in her essay “Abbottabad Pastoral,” that Pakistan has an “elusive, paradoxical nature. In the Pakistan that I know, wherever there’s beauty or charm, bullets and disaster aren’t far away.” But Khan is adamant that this can improve. There must be a global effort, he says, “to touch the lives of the people. You’ve got to make sure there are x-ray machines and MRIs in rural hospitals” as well as employment for locals, and funds for education. He’s constantly looking for ways to improve lives. And he cites benefits beyond the borders of his country: “Americans are losing out,” he opines, if they don’t take advantage of business with Pakistan. Though the United States is the leading trading partner of Pakistan, given the tumult in the region, he’s had to contend with some stereotypes and resistance over the years.

A few years ago, for instance, negotiations were under way for the undersea fiber optic cable. Representatives from a cable company wanted the SAIF team to travel to Dubai to sign the contracts. After all, they explained, the state department had issued a travel advisory for Pakistan. It would be wiser to meet elsewhere. No one went to Islamabad.

Khan keeps a serious face as he tells the next part of the story. “I said, “Gentlemen, I have a better suggestion. Why don't you guys give me a 20 percent discount on the contract, and I’ll pay for your trip on the space shuttle to the moon. We’ll go and sign the contract there, and guess what—there’s no Taliban there—yet!’” He smiles behind his thick, white mustache.

“I told them, ‘If you want it, you come to Pakistan.’” His strategy worked. Representatives from the cable company flew to Islamabad, and even though the negotiations could have been accomplished in two days, Khan invited the team to stay for five, so he could show them his beloved city. The team was charmed by Islamabad and became “ambassadors” for Pakistan, Khan says.

He doesn’t deny the conflicts. But he wishes that the world could see more positive stories about his country. “Good news doesn’t sell. But believe me, it’s not that bad. The fighting is up in remote areas, not in Islamabad, where the stock exchange is booming.”

That’s not to say that the SAIF Group shies away from places where danger is real. In one rural area, people were forced to travel three roundabout miles to get to town or else cross a rickety, unsafe bridge. City officials claimed their hands were tied because the Taliban would blow up any new bridge they built.

“But we built the bridge,” Khan says proudly. “People talk of helping the poor,” he says, “but we’re finding a way to do it.”

Along these lines, the SAIF Group also runs the Saifullah Foundation for Sustainable Development, which focuses on improving the lives of women and children through healthcare, education, and agriculture. It’s fitting that this organization was founded by the company’s original matriarch, Begum Kulsum. Afridi encourages stories about this type of progressive work, part of the fresh paint on Pakistan’s ever-evolving canvas. She thinks that in addition to pioneers like Khan’s mother, the global environment and social media have increased Pakistani women’s “awareness of what’s possible.” Today, women work in every department of the SAIF Group.

“In our country,” Khan says, “we have a saying: You educate a woman, you educate a generation.”

You only have to look at the Khan family to see this in action. Khan’s niece, Hoor Yousafzai, who holds a master’s degree in economics and computer science, is a CEO within the SAIF Group. And her son, Ali Yousafzai, is carrying on the family tradition. He’s currently a senior at CMU, the third generation to bring Pakistan to Pittsburgh.

Ali Yousafzai says he loves CMU, but he misses his mother’s chicken curry. He also misses hiking in the Margalla Hills National Park on the edge of Islamabad. He misses bowling, playing PlayStation, going out for dinner with friends. And he misses his pet Rottweiler.

“Fluffy’s very friendly!” he insists. Although he was pleased to find that Pittsburgh is almost as green as his hometown, someday he plans to return to Pakistan, and to Fluffy, and to the family whose legacy he will continue.

Yousafzai describes Khan as a loving uncle, someone he could always visit at the SAIF offices, an entrepreneur with the kind of business skill he envied. Now an electrical and computer engineering major, Yousafzai talks eagerly of his interest in entrepreneurship—he envisions starting his own company to bring software and web application products to the market. At CMU, Yousafzai frequently visits the Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, meeting with mentors who can advise him about his plans. The Center helps students, faculty, staff, and alumni bring promising ideas to fruition in the marketplace.

Yousafzai is impressed by his uncle’s impact on their country and keen to make his own contribution. SAIF Power is particularly inspiring to him, as its gas and steam turbines help avert electricity outages in rural areas. “People think Pakistan is just a desert with camels,” he says, but it’s much more than that. “It’s still a developing country,” Yousafzai concedes, “but there’s a lot of potential. We just need more investment in education to make sure that public schools are good quality.” And like his uncle, Yousafzai explains that his own plans are based on “finding something that’s missing and filling the gap.” The best advice his uncle ever gave him? “Follow your passion.”

Khan has taken his own advice. Even though he pondered retiring at 55, he found he didn’t really want to. He’s now 64 and says he has no regrets. In fact, going to the office still feels like stepping into a “big oxygen tank.” He’s followed his mother’s trajectory, receiving the Sitara I Imtiaz, another of Pakistan’s highest civil awards, but he doesn’t plan on stopping soon. These days, he continues to run the SAIF Group; speak at conferences; and, of course, look for new alliances, the next big thing, the next way he can fill a need for his country.

And what of his mother’s four admonitions? Khan eventually did get married to a Pakistani woman. Although he’s not a skier, he did vacation in Miami during his sophomore year, explaining to his mother that lifeguards would keep him safe and that it would look quite odd to wear regular clothes on the beach. She relented.

But what’s clear above all is that this Carnegie Mellon alumnus did not fail. “I’ve achieved, I’ve traveled, I’ve been on advisory councils for the government. I’ve been able to give back,” he says. His nephew is poised to follow in his footsteps. The Khan family is part of the unfinished painting Afridi so beautifully describes, a force for progress in a nation still feeling its birth pangs.