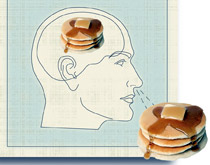

Most Saturday mornings find Nathan Urban in the kitchen flipping pancakes. While his wife, Kristen, and three sons awaken to the mouthwatering aroma of sizzling batter wafting through the air, Urban is reminded of his work. As head of the department of biological sciences and a researcher in the Center for the Neural Basis of Cognition, he recently shed light on a stubborn question about how the brain cells that detect smells function.

In experiments designed to emulate smell-cell activity in the brain of a mouse, Urban found that, unlike transistors-which respond identically to a given electrical current-look-alike mouse cells respond differently when stimulated by the same electrical current. The finding is significant because differences in output previously were attributed to limitations of laboratory methods or detection equipment. By using an advanced laboratory technique, Urban is able to precisely control the electrical input and measure the electrical output signals of different cells. His research demonstrates that the variation of response between cells increases the brain's bandwidth to detect more subtle and complex smells.

In collaboration with post-doctoral researcher Krishnan Pradmanabhan, Urban reported his findings in Nature Neuroscience, a peer-reviewed journal that is considered to be the voice of the worldwide neuroscience community. The understanding of diversity among cells could help researchers better understand neurological disorders like epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and schizophrenia.

At the Urban household, though, it has different implications. When his son Theo was still in diapers, Urban would encourage him to savor the aromas from the griddle or from the spice rack as he cooked. Theo's early introduction to the delightful complexities of his sense of smell has made him, as described by his mom: "Our family's most adventurous eater."

-Tom Imerito