Four mechanical engineering graduate students from Carnegie Mellon walk into a restaurant in Albuquerque, N.M. They traveled across the country to present their work in a micro-device design competition hosted by Sandia National Laboratories, a science and engineering lab that is a contractor for the U.S. Department of Energy.

For Sameer Shroff and Andrew Fassler, who are from the United States, the restaurant choice is nothing special. But for Ying-Ju Ivy Yu, who is from China, and Rui Yang, who is from Taiwan, this will be their first sampling of Mexican cuisine. After tasting fresh, hot sopapillas with rice and beans, they agree that they must have Mexican food more often. Throughout the meal, talk never strays much from the competition. The students rehearse their presentation several times—getting all the extra practice they can between bites.

The competition asks students from U.S. and Mexican universities to design very small mechanical devices, such as surgical tools. There are two categories: novel design and educational. For the Carnegie Mellon students, the competition is half of the coursework for a graduate class, “Special Topics in Experimental Micro- and Nano-Mechanics,” taught by Maarten de Boer, in which students learn the principles of designing small mechanical devices.

All of the students proposed a device to design for the contest. After a vote, Shroff’s concept was selected for entry into the educational category. Their device was designed to allow students on the high school, college, or graduate-school level to explore how changes in mass and stiffness affect a mechanical system, such as a water wheel.

Because Shroff’s design was chosen, he was named team lead, and he delegated the tasks each student had to perform in order to meet the deadline. They worked furiously for nearly a month, spending late nights in the laboratory solving complex equations. In fact, says Shroff, because of the tight timeframe, they ended up solving one problem by rolling up their sleeves and doing the complex math themselves, rather than waiting to buy, install, and learn software.

“We just did it,” he says. “It was certainly gratifying seeing a direct application of theory to real-world design!”

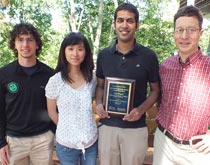

Now it’s time to find out whether that hard work paid off as they present their work, “Measurement of Adsorbed Species by MEMS Parametric Resonance,” for an audience of professional colleagues. The news is good. The Carnegie Mellon quartet beats out about a dozen other schools to take first place in Sandia’s educational category.

—Lorelei Laird (DC’01)

Related Links:

CMU Team Wins First Place at MEMS University Alliance Design Competition

University Allliance - Design Competitionn