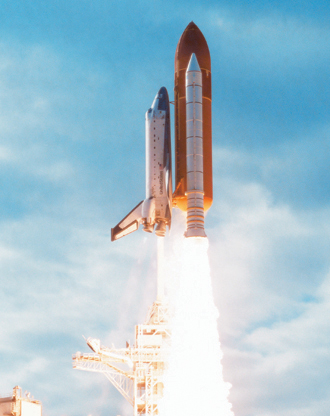

As the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) prepares the space shuttle Discovery for its December mission, the adequate and accurate calculation of risk—which ultimately translates into the safety of the astronauts on board—will be critical when making the final decision to launch.

To avoid potential New Year's Eve computer glitches, NASA will be under pressure to embark on the 12–day mission before December 18, 2006. Paul Fischbeck, professor of Engineering and Public Policy, hopes the added pressure doesn't result in poor decision–making.

To illustrate, Fischbeck begins by recounting NASA’s decision to launch the Challenger spacecraft on the morning of January 28, 1986.

“They knew they had trouble with the seals,” Fischbeck recalls. “One of the criteria was to launch only when the temperature is above 50 degrees Fahrenheit. They had launched before when the temperature was in the upper 40s, but on that day, the temperature was below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. The engineers advised management not to launch. Unfortunately, NASA’s management ultimately rejected that input.”

Challenger exploded 73 seconds after liftoff. A presidential commission report on the accident later confirmed that the cause of the explosion was the failure of an O-ring in the joint between the two lower segments of the right solid rocket booster. Freezing temperatures prior to the launch had damaged the rings, allowing ignited gases to burn into the external fuel tank.

Fischbeck believes that what happened to the Columbia spacecraft in 2003 is another example of the space agency’s failure to adequately consider risk when deciding a course of action. During the early part of Columbia’s ill-fated flight, a briefcase-sized piece of foam fell off and hit the orbiter.

“So they [NASA] held meetings,” said Fischbeck. “The engineers said they wanted to use satellites to look at the damage. NASA’s management responded, ‘Let’s not worry about it.’”

Columbia and its crew perished upon reentry into the Earth's atmosphere; the shuttle burned up over Texas when superheated gases penetrated its wing. And Fischbeck, who had begun looking at debris coming off the external tank of the shuttle when he was in graduate school, suddenly found himself in the national spotlight.

“We had figured out in 1991-92 that a disaster like that was a real possibility,” said Fischbeck. “We had modeled how Columbia was lost, so when it actually happened we got a lot of notoriety.”

An independent investigation into the cause of the Columbia accident concluded that it was foam insulation falling off the tank that had damaged the sensitive thermal protection system on the orbiter.

The stinging 248-page report detailed eight separate “missed opportunities” during the 16-day flight, including a NASA engineer’s unanswered email four days into the mission asking Johnson Space Center if the crew had been directed to inspect Columbia's left wing for damage, and NASA’s flight chief’s failure to accept the U.S. Defense Department's offer to obtain satellite imagery of the damaged shuttle.

The report went on to say the NASA organizational culture had as much to do with the accident as the foam.

“Managers’ tendency to accept opinions that agree with their own dams the flow of effective communications,” the report said. It also stated that NASA relied on past successes as a substitute for sound engineering practices.

Yet two-and-a-half years and billions of dollars later, NASA “launched Discovery, and they still hadn’t fixed the problem,” according to Fischbeck. During Discovery’s return-to-flight mission on July 26, 2005, a one-pound piece of foam broke loose from the external tank, just missing the orbiter.

“In 2005, they had a shuttle equipped with all these cameras, which provided unprecedented information on the condition of an orbiter in space,” said Fischbeck, “But they hadn’t fixed the problem. They were so lucky that time.”

NASA's managers appear to be more vigilant these days. They removed the worrisome foam ramp from the external tank before Discovery launched on July 4, 2006. And a small hole on Atlantis, believed to have been caused by some space debris during its September mission, is being carefully studied.

With more than a dozen missions remaining before the shuttle fleet’s planned retirement in 2010, has NASA learned its lesson? “Let’s hope so,” said Fischbeck.

Related Links:

Engineering and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon

Paul Fischbeck

Astronaut bio: Judith Resnick

Welcome to NASA

Kennedy Space Center