The teenager heads out the front door of his family's modest suburban Pittsburgh home and cuts across the lawn. Once on the street, he walks briskly, dribbling his basketball until it gets too hilly. Then, he cradles it as he hustles his way through the neighborhood. After he crosses a busy two-lane artery, he resumes his dribble all the way to the outdoor court near the local fire hall. For hours and hours, he stays there, playing pickup ball with his friends—shooting, passing, and dribbling away the summers of his youth.

"One hoop was two inches too high and the other was too inches too low," Herb Sendek recalls, clearly amused at the memory. "There were a lot of guys who wanted to play, but it was only the winners who stayed on. If you wanted to keep playing, you always hoped to shoot at the basket that was two inches too short because that helped the shooting percentage. If a guy could shoot well on the other one, you knew you had a player in the house."

Two inches too high. Two inches too low. Driven to stay on the court, it didn't matter which goal he faced. Sendek had to adapt.

The son of a basketball coach, Sendek has always felt the game flow in his veins. His childhood bedroom, a shoebox roughly the size of the three-second lane on a court, was plastered with photos of ballplayers pulled from issues of Sports Illustrated. "When he was very young, he'd tag along with me," says his father, Herb Sendek Sr., a retired mathematics teacher who coached in western Pennsylvania's junior college ranks. "I'd come home, pick him up, and take him to practice. He didn't mind missing meals."

"By the time I was in diapers, I was running around gymnasiums rather than playing in sandboxes," says Sendek.

The youngster loved the game. He never shied away from picking up the phone and talking with players and coaches who were looking for his dad. "He knew the ballplayers," says Sendek Sr. "I'd hear him converse with the players. He did that so well. Where he picked that up, I don't know. One time, a coach called me when I wasn't home. He told me later that he talked to Herb and was amazed at how well he was able to tell him about the skills of his own players. We're talking about a kid who was only 13 years old!"

Sendek's mom, Janet Sendek, wasn't surprised. "What did you expect..., he had a full-size basketball in his playpen from the time he was six weeks old."

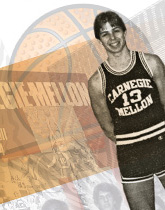

Actually, there was a lot to expect—Sendek never gave a reason for anyone to believe otherwise. As a high school student, the two-year letterman and senior captain on the Penn Hills Indians' basketball team was class valedictorian. For his efforts, Sendek earned an appointment to West Point, though he ultimately chose Carnegie Mellon, where he was awarded a Carnegie Merit Scholarship. Naturally, the Industrial Management major played for the Tartans basketball team.

Beginning his junior year, though, the 6-foot-1 guard and the rest of the squad found themselves suiting up for a new head coach. Sendek was a capable reserve as a freshman and sophomore, but he saw very limited action as a junior under the new coaching regime. By the first week of Sendek's senior season, he and two other members of the varsity squad were cut. Meanwhile, Greg Gabriel, a standout senior guard and Sendek's roommate, quit, partly out of loyalty to his friend and teammate.

"It was devastating," says Sendek, quietly. Wanting to keep the game he loved so much a part of his life, he visited nearby Central Catholic High School. There, he arranged to work with the boys' varsity and junior varsity teams as a volunteer assistant coach.

Despite the upheaval to his playing career, Sendek's performance in the classroom remained unflappable. Westinghouse Corp. soon came knocking, hoping the summa cum laude student would join their ranks. They gave him 30 days to consider a substantial job offer. He decided to turn it down. "By the spring of my senior year," says Sendek, "I knew for certain coaching was what I was going to do."

Sendek's dad has a prized possession, but it's not a basketball memento. It's one of his son's college papers that is kept safely tucked away. "Herb wrote this paper for one of his college classes. It's 26 pages long and talks about our families' heritage, about how my father and Janet's father worked and struggled in the coal mines. It left a strong impression with Herb's professor, who said it was one of the best papers he'd ever read."

The paper chronicles life in the bituminous western Pennsylvania mines for Sendek's grandparents. He says images of his grandparents remain quite vivid. "I remember them when I was a little boy, absolutely. You talk about tremendous sacrifice. I can remember hearing about one of my grandfathers setting his alarm clock to get up and work the midnight shift, about both of them coming home and only being able to see the whites of their eyes since the mines left you covered in soot. I don't think they had an indoor shower on my father's side for a long time. [His dad had to wash outside.] The bathroom was outside, too."

After getting cut from the Tartans' roster, Sendek didn't waste time feeling sorry for himself. Blessed with a work ethic passed down from the tough Slovak generations who preceded him, he remained focused on his academics, thriving on Carnegie Mellon's demanding quantitative business curriculum and accompanying classroom competition.

"I've never met anybody at Carnegie Mellon or probably anywhere else in my professional life who is so focused," says Gabriel, Sendek's teammate for three seasons and Scobell House co-habitant for 3 years. "Herb is highly intelligent, but so are a lot of other people at Carnegie Mellon, which meant the competition for grades in a class are skewed. Herb liked to call those people 'curve busters,' the ones who would be at just a completely different level than anyone else."

Which leads to the obvious question: Was Sendek a curve buster himself? "Well, I don't know if he ever received a 'B' on a report card, I can tell you that," says Gabriel, who earned his Industrial Administration degree in 1985 after leading the Tartans in points, assists, and steals in 1983—84. To date, he remains eighth on the school's all-time career assists list.

When Sendek wasn't immersed in classwork, he was at practice with Central Catholic. Such a schedule left little time for socializing, even when his parents came to visit. "We'd come down to campus on a weekend to take him and Greg out to dinner, but he'd say he didn't have time and that he had to study," says Sendek's mom. "They'd open that door six inches and Herb would hand me a garbage bag with dirty clothes. I'd give him a bag of clean clothes and maybe hand him and Greg some fast food or a care package. Then he'd say, 'Good-bye. I'll see you later.' When he did come home for a weekend, I'd ask if he'd like to go see a movie or ask somebody out. And he'd say, 'Sorry mom, I can't. I have to study.'"

Dedication to academics might sound unusual for a young man who knew, deep in his heart, that he was on the path to coaching. Really, what difference did it make if he didn't get that "A" when there were X's and O's to diagram in his future?

Gabriel, a self-employed businessman who remains close to his former teammate (Sendek is godfather to Gabriel's teenage son), is succinct in his response: "Whatever Herb takes on, he wants to be the best he can be. I guess you can call it a drive for success."

It was that single-mindedness that compelled Sendek to turn his back on the corporate world. After earning his degree in 1985 and declining Westinghouse's offer, he capitalized on a coaching connection with the director of the Five Star basketball camps, a prestigious summer destination for high school talent held in venues throughout the country. Sendek attended one of the camps as a scholastic player and absorbed speeches given by some of the game's most dynamic coaches, including a young college coach named Rick Pitino. Now that Sendek had decided on a coaching career, he asked the camp director to put in a good word for him with Pitino, who was beginning his first year as head coach at Providence College after two seasons as an assistant with the NBA's New York Knicks.

Pitino hired Sendek as a graduate assistant in 1985, but his foray into the college coaching world was hardly an easy layup. "Herb lived in the dorm. He had no transportation, no money, and ate in the school cafeteria," remembers Sendek Sr. "I'm thinking, 'Did he do the right thing?'" Sendek's mother was no more convinced. "We drove up 500 miles and left him on that campus," she says. "I'll never forget it. I cried for 12 hours all the way back home."

But entry-level coaching jobs don't come around very often in high-profile conferences such as the Big East, where Providence competed. "I had to give it a shot," says Sendek.

After four years there, the shots kept coming. He became an assistant for four years at the University of Kentucky; then, at age 30, he was named head coach at Miami of Ohio. In four years there he led the team to a Mid-American Conference title and garnered MAC Coach of the Year honors. His success there led to a coveted head coaching position in the elite ACC conference. Sendek coached North Carolina State from 1996—2006. During that time, he led the program to five consecutive NCAA Tournament berths and, in 2004, was named the ACC Coach of the Year. In demand whenever head coaching positions opened up, Sendek three years ago made his latest move by becoming head coach of Arizona State, which had a basketball program proud in tradition but in need of revamping.

In just three seasons there, Sendek has coached the Sun Devils to back-to-back 20-win campaigns for the first time in 28 years. A largely middle-of-the-pack program throughout most of its history in the UCLA—dominated Pac-10 Conference, Arizona State posted an impressive 25—10 record and a second-round showing in the NCAA Tournament this past season, its first appearance in college basketball's showcase event since 2003.

"Coach Sendek is more than a great coach," says Jeff Pendergraph, a senior forward who graduated in 3½ years with an economics degree last December. "He helped me grow as a leader. When I had a tendency to get frazzled on the court, he'd pull me aside and talk to me and get me to calm down and back on an even keel. I owe him so much."

A humble, studious-looking man, Sendek would appear just as at home in Cyert Hall, Posnar Hall, or any lab on Carnegie Mellon's campus as he does on the Sun Devils' sidelines. His teams are known for their fluidity on offense, which requires patience and precision passing while looking for a quality shot. Often, this comes after a sharp backdoor cut to the basket that leaves defenses helpless and confused. It's an approach that has earned the coach a cerebral reputation.

His cerebral reputation on the court and in the living room of potential recruits hasn't gone unnoticed by one of his old classmates, Buddy Hobart (HS'81), who is the founder of the Pittsburgh-based global business consulting firm Solutions 21. "Look at Herb's record," says Hobart. "He is an expert in recruiting and leading the Gen Y demographic." After Hobart pointed that out to his college friend, the two decided to collaborate on a new book, Gen Y Now (Select Press, 2009), which provides strategies for businesses in recruiting, training, and leading Gen Y (people born after 1976).

With 308 career wins and selection as one of the top 10 recruiters in the nation by Sports Illustrated, Sendek's Gen Y strategies seem to be working.

Chris A. Weber is a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer and a regular contributor to this magazine.