The year is 1989, and Renée Stout is contemplating taking a step that is dreamed of by nearly any artist: quitting her day job.

After the Carnegie Mellon art major earned her BA in 1980, she remained in Pittsburgh for the next five years, working at a thrift store while showing her artwork with a group of artists called “Visions.” Then she relocated to Washington, D.C. To pay the bills there, she worked a day job with the Montessori after-school program. But she also spent hours upon hours sculpting and painting in her bedroom. And it paid off—her work was included in a group show by the city’s well-respected BR Kornblatt Gallery.

That show has Stout standing at the edge of the two week’s notice precipice. Her inclusion was an unexpected surprise, and she admits she’s never enjoyed navigating the salesmanship side of the art world. In 1976, she arrived at CMU’s portfolio review toting an armful of rolled-up drawings—in contrast to the acetate-sleeved, zipper-encased presentations of her classmates. And, in 1989, it wasn’t she who approached the Kornblatt gallery. Rather, a friend, unbidden, took slides of her work to the gallery’s owner, who was so impressed that she showed up at Stout’s home to invite her to join the group show.

That show has Stout standing at the edge of the two week’s notice precipice. Her inclusion was an unexpected surprise, and she admits she’s never enjoyed navigating the salesmanship side of the art world. In 1976, she arrived at CMU’s portfolio review toting an armful of rolled-up drawings—in contrast to the acetate-sleeved, zipper-encased presentations of her classmates. And, in 1989, it wasn’t she who approached the Kornblatt gallery. Rather, a friend, unbidden, took slides of her work to the gallery’s owner, who was so impressed that she showed up at Stout’s home to invite her to join the group show.

A few months later, Stout received another call from the gallery. They wanted to bring her back, this time for a solo show. Stout knew that she would need extended, uninterrupted time to create enough pieces to fill the gallery.

And so: to quit, or not to quit? Seeking advice, she asks her mom, “What should I do?”

The answer was “the most amazing thing,” Stout recalls. “My mother, who always believes you should have a job, who believes in security … she asked me, ‘Do you know any artists who are making a living at it?’” Stout did and rattled off a few names. Her mother replied, “Well, what makes you think that you’re not supposed to be one of those people?”

Stout quits her job, especially because she’s also juggling another group show at the Dallas Museum of Art. In February 1990, that group exhibition is featured in Newsweek magazine. An image of Stout’s work is the sole photo featured in the article, a good omen of things to come. Indeed, when her solo show opens at the BR Kornblatt Gallery in 1991, it’s met with critical acclaim.

The years since have had ups and downs; Stout is as candid about droughts of attention and money as she is about floods of praise and recognition. But she has remained a fulltime artist throughout. Her work has been honored with an impressive slate of exhibitions and awards, including the distinction of being the first American artist to show at the National Museum of African Art.

In recognition of Stout’s exceptional career, Carnegie Mellon awarded her a 2014 Alumni Achievement Award.

Her work defies easy categorization, as she is involved in several mediums: painting, sculpture, mixed-media, printmaking, photography, film, assemblage, and even performance art.

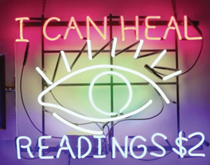

Stephen Bennett Phillips, a renowned D.C. curator who has lectured around the United States, was among those who first took note of Stout in the 1990s. “Early on, what impressed me about her work was the complexity of it, the layers,” he says. “It really is a type of work that you have to spend time with to absorb.” Phillips, who eventually curated Stout’s 2002 exhibition at the Belger Art Center, is referring to both the detail of her construction (which might include found objects, hand-drawn lettering, or a paint mixture made with dirt) and the cultural, political, and personal depth of her ideas. Her work draws heavily on African culture and religion to explore everything from current events to spirituality to personal identity.

Stephen Bennett Phillips, a renowned D.C. curator who has lectured around the United States, was among those who first took note of Stout in the 1990s. “Early on, what impressed me about her work was the complexity of it, the layers,” he says. “It really is a type of work that you have to spend time with to absorb.” Phillips, who eventually curated Stout’s 2002 exhibition at the Belger Art Center, is referring to both the detail of her construction (which might include found objects, hand-drawn lettering, or a paint mixture made with dirt) and the cultural, political, and personal depth of her ideas. Her work draws heavily on African culture and religion to explore everything from current events to spirituality to personal identity.

Stout describes herself as being in possession of a hyper-awareness that “can be paralyzing” in combination with worldwide cycles of violence and instability. She responds through her art, using her work as “a vehicle [to] process how I’m feeling about what I’m seeing,” whether an international news story or an article in Psychology Today.

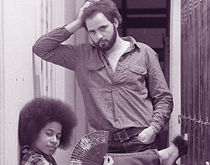

Her former classmate and longtime friend Frederick Mershimer (A’80), also a fulltime artist, has watched Stout’s work mature from her unpredictable art-school style (everything from acid-mixed paint to Hopper-style realism) to her more focused, if equally eclectic, current work. The common thread across the years, he points out, is Stout’s inquisitive nature. “She will always restlessly be searching,” he explains, constantly asking, “What is my place in the world?” Her work encourages viewers to ask similar questions, often by challenging them to look at an idea or object they would otherwise ignore.

But while Stout’s work may be challenging, it isn’t lecturing. She doesn’t take herself or her art overly seriously. “When we find really pretentious art-speak, we’ll call each other and go, ‘Listen to this!’” Mershimer laughs. He and Stout first bonded when they locked skeptical eyes in their freshman design class. The class was listing the possibilities they saw in an abstract yellow shape. Mershimer and Stout met after class and agreed: They’d seen nothing more than the shape.

It might be tempting to interpret their realization as a lack of creativity. But Stout’s work—in its evolving, layered forms—indicates that she doesn’t suffer from a dearth of imagination. Instead, she is interested in drawing inspiration from reality itself. Walking down the street with her, Mershimer explains, is an exercise in seeing. Sometimes, Stout will snap a photo, perhaps of a patina of paint and rust on a steel girder; but just as often, she’ll reach down and pick something up—a lost hair extension, a stray rusty bolt—and include it in a piece of artwork.

In material and idea, Stout’s art incorporates both the beautiful and the rough-hewn. The result, Phillips notes, can be tough to live with. You certainly won’t find a Stout piece in a corporate hotel lobby. But the artwork’s lack of easy palatability isn’t a bad thing; in fact, it may be exactly what makes it worthwhile. In Phillips’ words, “Good art should be tough.”